How Towels are Manufactured

Bath towels are woven pieces of fabric either cotton or cotton-polyester that are used to absorb moisture on the body after bathing. Bath towels are often sold in a set with face towels and wash cloths and are always the largest of the three towels. Bath towels are generally woven with a loop or pile that is soft and absorbent and is thus used to wick the water away from the body. Special looms called dobby looms are used to make this cotton pile.

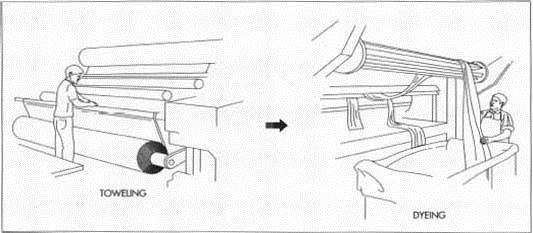

Bath towels are generally of a single colour but may be decorated with machine-sewn embroidery, woven in fancy jacquard patterns (pre-determined computer program driven designs) or even printed in stripes. Since towels are exposed to much water and are washed on hot-water wash settings more frequently than other textiles, printed towels may not retain their pattern very long. Most towels have a two selvage edges or finished woven edges along the sides and are hemmed (cut and sewn down) at the top and bottom. Some toweling manufacturers produce the yarn used for the toweling, weave the towels, dye them, cut and sew hems, and ready them for distribution. Others purchase the yarn already spun from other wholesalers and only weave the toweling.

Towel Weaving History

Until the early nineteenth century, when the textile industry mechanized, bath toweling could be relatively expensive to purchase or time-consuming to create. There is some question how important these sanitary linens were for the average person—after all, bathing was not nearly as universally popular 200 years ago as it is today! Most nine-teenth century toweling that survives is, indeed, toweling probably used behind or on top of the washstand, the piece of furniture that held the wash basin and pitcher with water in the days before indoor plumbing. Much of this toweling was hand-woven, plain-woven natural linen. Fancy ladies' magazines and mail order catalogues feature fancier jacquard-woven coloured linen patterns (particularly red and white) but these were more likely to be hand and face cloths. It wasn't until the 1890s that the more soft and absorbent terry cloth replaced the plain linen toweling.

As the cotton industry mechanised in this country, toweling material could be purchased by the yard as well as in finished goods. By the 1890s, an American house-wife could go to the general store or order through the mail either woven, sewn, and hemmed Turkish toweling (terry cloth) or could purchase terry cloth by the 'yard, cut it to the appropriate bath towel size her family liked, and hem it herself. A variety of toweling was available—diaper weaves, huckaback’s, "crash" toweling—primarily in cotton as linen was not commercially woven in this country in great quantity by the 1890s. Weaving factories began mass production of terry cloth towels by the end of the nine-teenth century and have been producing them in similar fashion ever since.

Towel Manufacturing Raw Materials

Raw materials include cotton or cotton and polyester, depending on the composition of the towel in production. Some towel factories purchase the primary raw material, cotton, in 500 lb (227 kg) bales and spin them with synthetics in order to get the type of yarn they need for production. However, some factories purchase the yarn from a supplier. These yarn spools of cotton-polyester blend yarn is purchased in huge quantities in 7.5 lb (3.4 kg) spools of yarn. A single spool of yarn unravels to 66,000 yd (60,324 m) of thread.

Yarn must be coated or sized in order for it to be woven more easily. One such industry coating contains PVA starch, urea, and wax. Bleaches are generally used to whiten a towel before dyeing it (if it is to be dyed). Again, these bleaches vary depending on the manufacturer, but may include as many as 10 ingredients (some of them proprietary) including hydrogen peroxide, a caustic defoamer, or if the towel is to remain white, an optical brightener to make the white look brighter. Synthetic or chemical dyes, of complex composition, which make towels both colourfast and bright, may also be used.

Design

Most towels are not specially designed in complex patterns. The vast majority is simple terry towels woven on dobby looms with loop piles, sewn edges at top and bottom. Sizes vary as do colours depending on the order. Increasingly, white or stock towels are sent to wholesalers or others to decorate with computer-driven embroidery or decorate with applique fabric or decoration. This occurs in a different location and is often done by another company.

The Towel Making Process

Towel Spinning

1 As mentioned above, some factories spin their own yarn for bath towels. If this is done at the factory, the manufacturer receives huge 500 lb (227 kg) bales of either high or "middling grade" (of medium quality) cotton for conversion into yarn (quality depends on the manufacturer and quality of the towel in production). These bales are broken open by an automated Uniflock machine that nips a bit off the top of each bale, opens it up and then lays it down. The Uniflock opening machine blends the cotton fibres together by repeatedly beating it so impurities fall out or are filtered out (these bales contain many impurities within the raw cotton). The more pure fibres are blown through tubes to a mixing unit where the cotton is blended together before they are spun. Higher quality towels use cotton with fibres that are blended together three times before spinning. In some factories, the cotton is blended with polyester during this blending process.

2 The mixed fibres are then blown through tubes to carding machines where revolving cylinders with wire teeth are used to straighten the fibres and continue to remove impurities before spinning. The cotton fibres while not yet yarn, are shaping up into parallel fibres in preparation for spinning.

3 These parallel fibres are then condensed into a sliver—a twisted rope of cotton fibres. These slivers are sent into another machine in which they are blended again and sent between other rollers for straightening. The ultimate goal is long, straight, parallel fibres because they produce stronger yarns. (Stronger yarns require less twisting which also produces strong yarns but makes them less soft and absorbent.) The fibres are wound on a large roll and sent on a cart and fed into the combing machine.

4 Fibres are combed here, further straightening the fibres with a finer set of wire teeth than used on the carding machine. Combing removes the shorter fibres, which are coarser and woollier, leaving the finer, longer, silkier cotton fibres for spinning into yarn. Once combed, the fibres are formed into a twisted rope sliver again.

5 The slivers travel to roving machines where the fibres are further twisted and straightened and formed into rovings. The roving frame also slightly twists the fibres. The result is a long roving of cotton, which is then wound onto bobbins in the final step before spinning.

6 Now the roving is ready for spinning. The bobbin is spun on a ring-spinning machine, which mechanically draws out or pulls the cotton roving out into a single strand. The fibres essentially catch one another to form one continuous thread and twists the thread slightly as it is pulled or spun. Once the yarn is spun, it is automatically wound on large wheels that resemble rounds of cheese when full of thread.

Towel Warping

Towel Weaving